Becoming Flexitarian: When Being Vegan or Vegetarian isn’t an Option

by Margaret McCasland

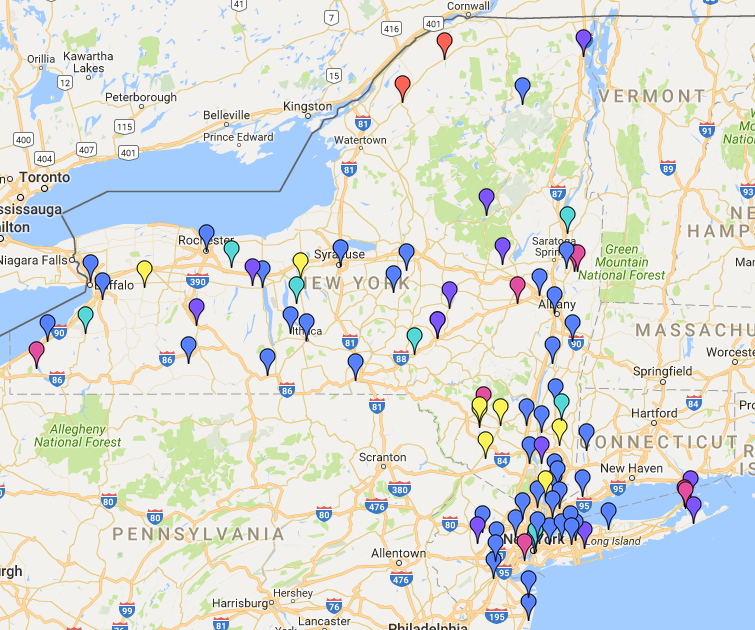

Ithaca Meeting

I grew up knowing where most of my food came from. Both sets of grandparents grew, gathered, fished or hunted much of their food: my father’s family in the Adirondacks, my mother’s family on the shores of the Atlantic. I was born in a fishing village, and we moved to a small farming hamlet when I was nine. Our milk and eggs came from neighbors’ farms, and we raised our own goats, ducks and geese. My father had an apiary adjacent to a neighbor’s produce farm, and we harvested as many vegetables as we could eat in exchange for the bees’ pollinating services.

During neighborhood canning bees, we put up a year’s worth of fruit and vegetables. In the late 50s, the women were thrilled when Sears started selling chest freezers, because it was easier to freeze most fruits and veggies than it was to use a pressure canner. My father ordered an extra large freezer so there would be room for the venison he brought back from his annual Adirondack hunting trip.

As a child, I ate what was put in front of me, with one notable exception. Since I spent much of my time after school and summers playing with baby goats, I would not eat their meat when they were slaughtered in the fall. So my father promised (lied) that he would find homes for all the kids. One of the kids did find a home at a friend’s house, so I believed him—until the year I killed a deer with my VW bus.

A neighbor and I butchered the deer. Once the meat was packaged and we sat down to eat some pan-fried liver, my neighbor could tell I was in shock and recommended a shot of whiskey. As soon as I began to drink it, I started shaking. Deer had just joined the goats on my “do not eat list.”

My husband was happy to eat venison, and I also brought venison to every pot-luck that winter. My half of the deer was soon gone, and I realized that the single deer my father killed every November could not have fed seven people for over six months. So I called one of my brothers and asked whether some of the “venison” we ate was actually goat meat. He said of course it was, but they had to pretend it was venison so I would eat it. In retrospect, I was grateful they had complied, instead of teasing me about eating “Alice” or “Whitey.”

I killed the deer in the early 1970s, while I was part of the “back to the land” movement in central NYS (hence all the potlucks). Vegetarianism was a new idea to most of us, but we were heavily influenced by two books: Frances Moore Lappé’s Diet for a Small Planet, which taught us how to get complete proteins from vegetarian diets, and the Moosewood Cookbook, based on recipes from a cooperatively-owned restaurant here in Ithaca. While Moosewood was famous for their vegetarian recipes, the restaurant served chicken and fish Friday and Saturday evenings. When it turned out that my children had trouble digesting milk, eggs, and some vegetable protein, I took a leaf from Moosewood’s book, and introduced them to fish and poultry.

This fall I discovered a name for the way I have been eating for decades: “flexitarian,” a combination of the words “flexible” and “vegetarian.” When doctors diagnosed my chronic joint pain as caused by multiple food intolerances a few years ago, my diet became extremely restricted. The flexitarian philosophy helps me enjoy the options I do have (occasional small portions of many foods). It also helps me understand and respect why some people choose to be vegan or vegetarian and others choose to eat responsibly-raised meat from mammals.

RELATED RESOURCE: What Is a Flexitarian? by Linnea Covington: www.thespruceeats.com/what-is-a-flexitarian-5095820