Silence and Music

by Adam Segal-Isaacson

Brooklyn Meeting

In 1952 John Cage composed 4’33” and it premiered the following year, performed by David Tudor. In this piece, a performer comes onto the stage, sits in front of a piano, and does not play for four minutes and 33 seconds. It is often referred to as “the silent piece,” but this is incorrect. There is no silence, and this was Cage’s intention: one should listen to the sounds that are present, the audience shifting in their seats and coughing, the birds outside the window, etc. One should pay attention to the sounds all around us.

In a lot of ways, this paying attention to what is around us is very much how little children behave, always noticing things and asking “what’s that?” This is precisely what Jesus meant when he said “except as ye become like little children.” We need to pay attention to what is around us all the time, and preserve that attention and wonder that we had as children. William Least Heat Moon, in Blue Highways, says, “When I go quiet I stop hearing myself and start hearing the world outside me. Then I hear something very great.”

Elsewhere in Blue Highways, William Least Heat Moon visits a monastery and partakes in a service. His comment in the book is “If there is a way to talk to the Great Primeval Ears — if Ears there be — music and silence must be the best way.” Nearly all religious traditions use music in some manner, often singing or chanting. These activities bring people together to be as one, as performers and listeners, especially as performing involves listening.

Cage often told the story of visiting a silent anechoic room, where every sound from outside the room was blocked out. He reported that he still heard two sounds, one very high pitched and one lower pitch. He was told that the high pitched sound was his nervous system and the lower pitched sound was his blood flowing. The presence of sound is all around and inside of us.

When we hear or play music, we are temporarily transported outside of ourself also. We can resonate with a larger world. This brings on a peaceful state, an internal quiet, even if the music is very energetic. Music brings people together, whether they are all playing in unison or harmonizing to create something an individual cannot do alone or even just listening to another person perform. Music is essentially a spiritual exercise, even music that seems to deal in nonspiritual matters.

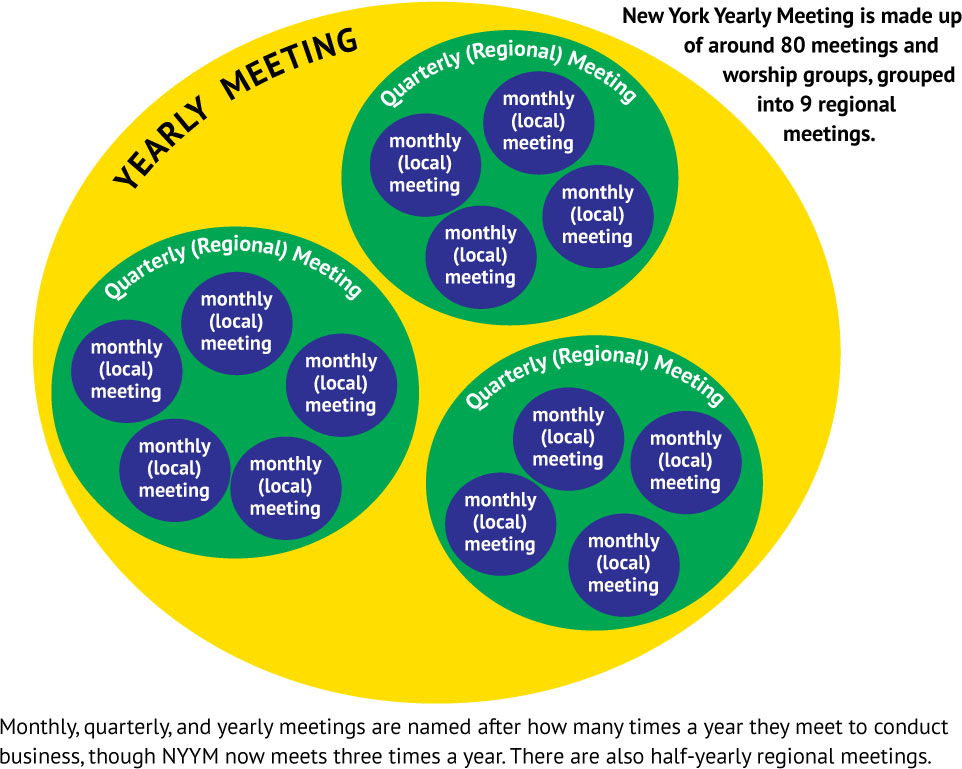

Quakers have traditionally put aside music and all the arts as distractions from spiritual life. But we have had great Quaker painters and Quaker musicians and composers, because they recognize the power of the arts to bring us something new, show us something about the world that we missed. Psalm 96 begins, “sing unto the Lord a new song.” We can make up the music we need and it can enhance our spiritual life. As Joe Vlaskamp, former General Secretary of New York Yearly Meeting, said, “We must never be satisfied with our spiritual level. We must always keep working on it.” And music can definitely help with attuning our spiritual attention.